Making Aliens 2: The Journey

The Repercussions of Planetary Settlement

The Repercussions of Planetary Settlement

by Athena Andreadis

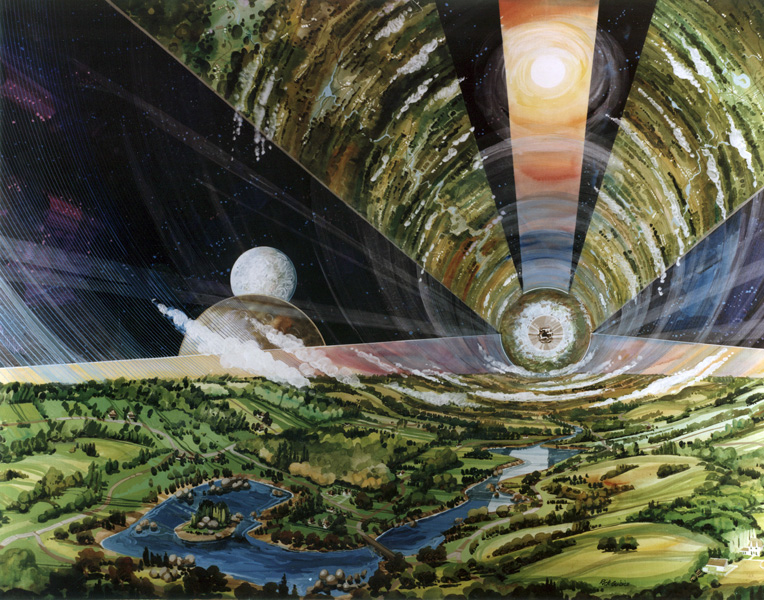

Art image: courtesy of NASA

Part 2: The Journey

The distances between star systems are truly vast. To reach Mars, our nearest neighbor, takes six months with our current propulsion systems. Even fusion drives or light sails will not shorten stellar trips by much. Truly exotic means, such as warp drives and stable wormholes, may never leave the realm of fantasy because of fundmental constraints — the lightspeed limit may prohibit the former, gravitational instability the latter.

So our current alternatives are the so-called “arks” or long-generation ships, which have to be enclosed and self-sustaining. The trouble is, we have never successfully engineered such a system, and the gobs of waste circling all our space vessels (particularly Mir) are sad witnesses to this fact. Biosphere 2, the first experiment to attempt creation of a totally enclosed, self-sufficient environment ended up with oxygen leaks, ecological breakdown, and severe carbon dioxide poisoning — plus virulent infighting among the participants.

Fortunately, Biosphere 2 was set up on Earth, where the surroundings could easily come to the rescue. That will not be the case for a ship halfway to another planet. In this respect, environmentalism with its insistence on recycling and conserving resources is not only a good strategy for our increasingly crowded planet but may also devise partial solutions to the problem of long, slow interplanetary journeys.

A long journey has additional associated dangers beyond ecological breakdown. One is the loss of biodiversity for all the species within the ship, including the human passengers. Another is mass psychosis, which can grip entire nations and will be far more dangerous in an isolated context deprived of outside corrective influences. Either can lead to the loss of technology, which has happened here on Earth as a result of discontinuities from environmental catastrophes, large-scale migrations or disruptive conquests. Classical Greeks and medieval Europeans forgot the sophisticated drainage and sewage systems of the Minoans and Romans, respectively; the Native Americans forgot the wheel; the Tasmanians forgot boats and even fire. The persistent refusal of NASA to study complicated human interactions in space, including sex, has left us ignorant and highly vulnerable in this respect.

If a spaceship loses technology, its passengers may not be able to survive on a hostile planet. Terrestrial examples of isolated settlements illustrate this danger. The medieval Norse settlements on Greenland as well as several European colonies in New England perished from malnutrition despite their high-tech beginnings. The Polynesians of Pitcairn and Easter Islands stripped their lush islands of vegetation (thereby breaking down their ecology, losing all trade and cutting their communication lines). Their solution was to resort to cannibalism, which led to their extinction within a few hundred years of their arrival.

Making Aliens 1: Why Go at All?

Making Aliens 2: The Journey

Making Aliens 4: Playing God I

Why would people who have spent their whole lives in a giant,

enclosed artificial environment in space want to land on and

settle a distant planet, especially when there is no guarantee that

any other worlds could support life from Earth? Nor can we

assume that those travelers would have the means or the

desire to terraform another planet.

Would it not be better and safer to roam the galaxy in a

giant space ark, seeing new places and avoiding potentially

hazardous zones. Being stuck on a single dirty little planet

for life seems boring and even cruel by comparison. Most

humans certainly lack a true appreciation for the wider

Cosmos being stuck on Earth, as an example.

Maybe this is why no ETI have made it clear that they

colonized Earth and the rest of the galaxy: Settling down

on a planet with all its uncontrolable natural dangers is both

unnecessary and so gouche. All the truly advanced beings

of the Universe would never soil their feet/tentacles/pads

with actual dirt and breath unfiltered air.

The other idea of adapting our descendants to live in almost

any cosmic environment also has merit, certainly at least to

ensure our survival and gain a knowledge of alien places that

no spacesuited astronaut ever could. It would be hard for the

galaxy to destroy a being that could live on the surface of

Venus or swims in the Europan global ocean or float in the

clouds of Jupiter, or dwells in space itself.

Personally I think that all these ideas will be surpassed by

our technological advancements, the kind that will create Artilects

and rearrange the Sol system into something more useful for

such intelligences.

Just because humans can barely conceive of how to do such

things and seem to inherit a rather primitive fear of the unknown

and those more powerful than us does not mean it has not already

happened somewhere or that our descendants will make them a

reality some day – especially when the galactic parameters change.

After all, we know that in just a few billion years Sol will make life

in the inner planetary system unbearable, so hopefully long before

then somebody has decided that the space program is in need of

a budget increase for conducting a mass exodus. Or maybe they

will find a way to keep our star and others under control and

fusioning properly way beyond its natural years.

Or maybe our descendants won’t need a sun at all.

The article considers some of the points you raised, wait till parts 4-6 of this essay (*smiles*). To address some of them:

This article does not discuss ETI. It focuses exclusively on human efforts and ones in the near future at that, which preclude the fancier flights of fancy. As a corollary of this, a being that could live under Jupiter-, Europa- or Venus-like conditions would not be human by any measure that counts.

You are making the assumption that the arcship has infinite renewable resources, almost certainly not the case. Also, countless natural dangers may lurk on planets — but they also lurk in space (radiation, impacts…)

Needless to say, I’m totally with you about the budget of the space program.

I am all for our Ark residents visiting other worlds and

gleaming resources from them – that to me is the point

of living on a giant spaceship rather than a single world,

that you don’t have to rely on one place for your food

and fuel, plus you get to see and learn about all sorts of

alien planets and can just leave if conditions become

dangerous.

That’s the one thing that really bugged me about Heinlein’s

otherwise really great SF novel Orphans of the Sky: Why

was most of the Ship windowless??

Leisurely ark visits would work if they had a lot of resources and could travel very fast. Distances between solar systems are enormous even at a significant fraction of the speed of light.

The lack of windows may have been an effort to decrease some of the dangers (radiation, impacts…). Also, in a very large ship. it might preserve the illusion of a complete world.

Brilliant! The observations here effectively enrich and round out the material presented here, particularly where the weighing of the benefits and drawbacks of extended interstellar travel against each other are concerned. The secondary concern of whether the advantages offered by remaining on an ark ship are superior to those which would be available on one world (which Walden2 astutely brings up) ties seamlessly into the primary issues. Also, an additional deciding factor, aside from the practical, technological and biological issues, the question of how well human beings would take to prolonged confinement prominiently stood out, to me. The pragmatic, inevitable and necessary considerations aside, the article does indeed hint at worlds of possibility.

Indeed, the human factor is the hardest to gauge and modulate. Isolation from context can lead to debilitating hallucinations and fugue states. This may be desirable in vision quests, but not in a de facto fragile starship. I believe LeGuin wrote a short story about this, though I cannot recall its title.

Any long term space voyage would have to take alot of physical needs into account, but also mental needs too. A generational ship in particular raises dangers of people becoming insane and killing each other, or perhaps just.. mentally inhuman. I’ve read about feral children who grew up and survived without normal human contact, and they act more like animals than humans. They’re physically like us, but they go around on all fours, have little to no language, they won’t even recognize themselves in a mirror.

Onto more essays…

Maybe that was the reason for the Oracle in the Star Trek TOS episode “For the World is Hollow and I have Touched the Sky”? The “instrument of obedience” provides a quite effective “corrective influence”!

I am very interested in closed-cycle life support systems. Without the means to produce oxygen, clean water, and food and to recycle waste on a spaceship, humans cannot survive in space for indefinite periods of time. This technology would benefit people on Earth greatly- if we could grow veggies on Mars, why couldn’t we end hunger on Earth?

This technology is ubiquitous in SF, even though most of the craft have FTL drives. Many spaceships have the means to maintain life support over long periods of time, especially exploration starships. Ships that do not must return to a spaceport or can city to restock after a few months, limiting them to short cruises. If one reads or watches such SF long enough, the question inevitably rises whether we can actually build devices like you see in the stories.

That said, propulsion is still one of the most important problems. Even generation ships require significant propulsive capabilities to reach a cruising speed of around 5% light-speed, and this outstrips the capability of nuclear-electric drives or solar sails. It isn’t just speed, either- rockets require unrealistically large amounts of reaction mass for such missions. Thus the popularity of reactionless “field drives” or mass-reduction devices in SF- while many spaceships in SF use conventional rocket thrusters for sub-light maneuvering, most spaceships in SF do not carry eight times (or more!) their structural mass and cargo in propellent!!

NASA, perhaps inspired by SF spaceship design, listed “discovering new propulsion methods that eliminate (or drastically reduce) the need for reaction mass” as one of the major goals of the Breakthrough Propulsion Physics project, the other two being “find a way to travel faster than light” and “find means to power these devices”.