The Hyacinth among the Roses: The Minoan Civilization

“But remember. Make an effort to remember. Or, failing that, invent.” – Monique Wittig, Les Guerillères

A story of mine, Dry Rivers, just appeared in Crossed Genres. It takes place in an alternate universe in which the Minoan civilization survives the Thera eruption. Coincidentally, I recently finished a book by Dr. Cathy Gere, Knossos and the Prophets of Modernism. The author discusses how the Minoan civilization served as a mirror that reflected the social biases of the era of its discovery – particularly of its idiosyncratic excavator, Arthur Evans.

A story of mine, Dry Rivers, just appeared in Crossed Genres. It takes place in an alternate universe in which the Minoan civilization survives the Thera eruption. Coincidentally, I recently finished a book by Dr. Cathy Gere, Knossos and the Prophets of Modernism. The author discusses how the Minoan civilization served as a mirror that reflected the social biases of the era of its discovery – particularly of its idiosyncratic excavator, Arthur Evans.

During the Bronze Age, several major civilizations blossomed contemporaneously around the Eastern Mediterranean. Many are familiar to most Westerners, if only by name – the Egyptians, the Sumerians, the Babylonians, the Hittites. But one was sui generis: the Minoans. Despite their extraordinary achievements, we know a lot less about them than we know about their neighbors. Their alphabet, Linear A, remains undeciphered. Nor do we know what language they spoke, though a few Minoan words still adorn the Greek tongue, such as thálassa (sea), lavírinthos (labyrinth, house of the double axes), hyákinthos (hyacinth) and kypárissos (cypress).

I have always been haunted and beguiled by that lost civilization. Most of my fiction, whether of the past or the future, fantasy or science fiction, involves the Minoans. Not only are they part of my biological and cultural legacy; they were also unique. Minoan art is instantly recognizable. It is possible that the Minoan civilization might have changed the flow of history, had it not been literally snuffed out by the apocalyptic explosion of the Thera (Santorini) volcano. Such was the magnitude of the catastrophe that it became a potent, defining myth that echoes down the ages, from Plato’s Timaeus to Tolkien’s Númenor: the drowning of Atlantis.

How distinctive and advanced were the Minoans? Cathy Gere argues that they were not. She suggests that the attempt to portray Minoan Crete as a pacifist, matriarchal haven of high sophistication is not supported by the archaeological evidence, but is mostly a fantasy (largely created by Evans) to act as a paregoric to a world reeling from several major wars. Gere’s style is vivacious, articulate, elegant – and she knows her history. It is also true that Evans’ reconstructions of the Knossos palatial complex and its frescoes were heavy-handed and arbitrary. And in time-honored archeological fashion, he withheld evidence and suppressed careers that contradicted his theories.

If Gere’s book were your only source on the Minoans, you would come away well informed, highly entertained and with the impression that they were just a standard variant of the Bronze Age Levantine cultural recipe. And since Linear A has not been deciphered, the Minoans cannot tell their own story. However, extensive frescoes and other artifacts that have been gradually emerging from Akrotiri, the Theran equivalent of Pompei, support major portions of Evans’ theory. Because burial under volcanic ash kept everything intact, no question of false reconstruction intrudes. The frescoes didn’t adorn palaces, but residential houses. This fact alone says something about the Minoan culture. So does the finding that the houses were multi-storied and had hot and cold running water – amenities forgotten by their successors and the rest of Europe for almost four millennia.

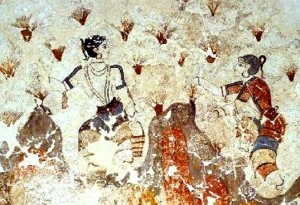

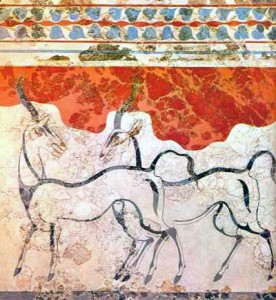

Even more indicative are the subjects of the frescoes: women gather saffron crocuses, boys box, crowds watch a regatta in a harbor, swallows intertwine over lilies, gazelles gambol. War is conspicuously absent – not a single battle scene, not one weapon, not even a chariot. Gods and kings, with their usual smitings, are also conspicuously absent. The focus is on nature and daily activities. This is true of all Minoan art, from frescoes to pots to seals. Too, there is a fluidity and exuberance that sets Minoan art apart from its Egyptian and Babylonian equivalents, which are oppressive with their will to power despite their beauty. And women are everywhere, always more prominent and detailed than the men, in stark contrast to their absence or subordinate status in the art of Crete’s contemporaneous neighbors.

In all other Bronze Age East Mediterranean cultures, the Great Goddess (Isis, Ishtar, Inanna) suffered dethronement at the hands of her Consort/Son. But in Crete she retained her primacy till the Mycenaeans arrived after the volcano eruption. This does not automatically imply that Minoans were matriarchal or that women enjoyed equal status in Crete. However, the scenes depicted in Minoan art suggest that women had significant rights and were active and valued participants in society. This is not surprising. Merchant and seafaring cultures are flexible and open to new ideas which they encounter willy-nilly, and Minoan Crete was both: the Egyptian, Babylonian and Hittite archives as well as the economic system deduced from the excavations indicate that the Minoan hegemony was light-handed, localized, sea-based and economic rather than military.

There is no doubt that Minoan Crete was not the utopian paradise that Evans envisioned. For one, if the Minoans had insisted on wearing only white helmets, they wouldn’t have lasted long enough to leave any legacy, wedged as they were between nations intent on empire. For another, the Minoans did have social classes: distinctions are clearly visible in the frescoes. However, it makes me happy and hopeful to think that there may have been at least one high civilization – the first one in Europe, in fact – that was not intent on conquest, enslavement and slaughter. That once perhaps there existed a people who were content to build and sail merchant ships, create ravishing art, sing harvest songs and love ballads… and gaze at the stars while sipping wine in the warm summer nights of the Aegean.

Further reading:

Frescoes:

Top, “La Parisienne”, Knossos, Crete; Middle, Saffron Gatherers (detail), Akrotiri, Thera; Bottom, Antelopes (oryx), Akrotiri

Another informative, well-balanced essay. As usual. Thanks!

I’m glad you enjoyed it, Calvin! So few people know about the Minoans, the Sogdians, the Mohenjo-Darans, the Etruscans… Lack of historical knowledge not only makes us repeat mistakes ad infinitum — it also impoverishes speculative literature. Peggy Kolm remarked to me that almost all of alternate history is either US civil war or 20th century US/Europe. So much for the genre expanding one’s horizons!

How lovely and hopeful an essay! And the Minoan women, how beautiful, with such a sweet but strong, intelligent expression!

Yes… the frescoes are really exquisite. You never forget them once you’ve seen them. They lodge in the mind, in the heart… and in the solar plexus.

I want to add my kudos on this essay. I’ve always been fascinated by the Minoan myth…and its good to hear that not everything was mythical.

No, not everything. Myths and grandmothers’ tales have a disquieting way of always containing kernels of fact. It’s hard to determine what is fact, though, on fragmentary evidence without imposing parochial biases (including the biases of the storytellers). Particularly thorny are interpretations of civilizations who had no written language or whose script remains undeciphered.

I enjoyed that story Athena and I’m glad to see it published.

I will look up the author you recommend! I find Minoan Crete quite fascinating and their art is breathtaking.

Yes, I hope that at least some pieces of that universe you saw come to life gets to see the light of day!

Speaking of women from antiquity, here is a brief article and trailer clip about the upcoming film on Hypatia of Alexandria titled Agora:

http://philosophyofscienceportal.blogspot.com/2009/08/science-vs-religionhypatia-of.html

I am very curious to see how they handled this whole subject. At least it will make some people aware of Hypatia and places like the Library of Alexandria.

I read about the film. But it shows her as young and beautiful (perhaps to accentuate the tragedy of her loss) — and did they tack the inevitable love story on?

Well of COURSE Hypatia was beautiful, Athena. Model types

always have the best adventures, now or then.

If the records are to be believed, the real Hypatia did have a

fair number of suitors, but she rejected them all in the pursuit

of knowledge. Supposedly she even showed her feminine

hygenie project to one persistant male to turn him off.

I read one article about Agora that says it is a story from the

perspective of one of Hypatia’s male slaves who was secretly

in love with her.

I fear this may be the antiquity version of District 9. But one

saving grace for Agora is that it will make people aware of the

real Hypatia and what she apparently stood for.

A book that was just recommended on the History of Astronomy list:

Hypatia of Alexandria: Mathematician and Martyr, by Michael A. B. Deakin. Prometheus Books, 2007. Hardcover, 231 pages, $28.00. ISBN: 9781591025207.

A detailed review of this book is by the Mathematical Association of America here:

http://www.maa.org/reviews/hypatiadeakin.html

I know this is about Iraq but I felt it important enough to share here, as so many aspects of our various cultures and their heritages are threatened:

http://philosophyofscienceportal.blogspot.com/2009/09/war-and-cultural-heritage.html

Indeed. The looting of the Baghdad museum while US soldiers guarded oil fields for the Texan barons; the blowing up of the Bamiyan Buddhas and the destruction of the Kabul museum by the Taliban; the flooding of archaeological sites in China, India, Turkey… we’re truly fouling our own nest to the point of no return.

I enjoyed your story very much. I’m an undergrad, and have only briefly touched on the Minoans and what is known about them in class – and with four books to read a week have no time to dive into my own research, argh – and your essay about them was wonderful to read.

I’m glad you liked the story, Marie! It’s part of a much larger cycle, extending from the past to the far future. I’ve been publishing bits and pieces, hoping that at some point I’ll be able to complete the novels and have them see the light of day.

People often compare modern America to ancient Rome, but maybe the USA is closer to ancient Athens, which according to this book might not be the best thing:

http://philosophyofscienceportal.blogspot.com/2009/10/athens-and-current-historynew-book.html

I wish these books would better serve as warnings from history, but the people who need to know this stuff never read it or realize what is going on until it is too late, then we all suffer and just keep going through the same rises and falls over and over for millennia.

I wonder – are we unique when it comes to having continually cyclical societies, or is this the norm for any true civilization no matter where you go in the Cosmos? Is it perhaps even healthy overall for a society to grow and decline periodically, like hitting a refresh button on a video game, rather than allow a culture to stagnate over time due to age and complacency, leading to eventual extinction down the road?

Or am I just being way too humanocentric?

Some of the points of the book are old hat (helmet?) for Greeks, though they might be new to Americans. Also, every historical analogy is inexact — some portions fit better than others.

Jared Diamond wrote a sequel to his Guns, Germs and Steel bestseller titled Collapse, in which he discusses the fall of several civilizations from a relatively “holistic” viewpoint.

I suspect that human civilizations, at least, are cyclical. I don’t know if this is true of non-human sapients. It will partly depend on their biology and ecology, I suspect, which will largely dictate their technology and their responses to it.

The Fall of the Maya — New Clues Revealed?

NASA Science News for October 6, 2009

Archeologists are using NASA satellites and supercomputers to crack the mystery of the ancient Maya. New findings suggest the Maya may have played a key role in their own downfall.

FULL STORY at

http://science.nasa.gov/headlines/y2009/06oct_maya.htm?list1094208

Check out our RSS feed at http://science.nasa.gov/rss.xml!

Diamond includes the Mayans in his discussions in Collapse, and so does Mann in 1491. The theory that they contributed to their downfall is not new. There are several tributaries that could have fed into the disaster: exhausting the soil, being too top-heavy as a society, the constant civil wars between princelings of the city-states. Add a persistent drought to these conditions and you get the resulting collapse.

All these histories, from the Greeks to the Mayans, are cautionary tales. But we never pay heed. At this point, both of these paradigms are poised to replay at a global level.

Portrait of a Priestess: Women and Ritual in Ancient Greece

Joan Breton Connelly

Winner of the 2008 James R. Wiseman Book Award, Archaeological Institute of America

Winner of the 2007 Best Professional/Scholarly Publishing Book in Classics and Ancient History, Association of American Publishers

One of New York Times Book Review’s 100 Notable books of 2007

464 pp. | 8 x 10 | 27 color illus. 109 halftones. 3 maps.

http://press.princeton.edu/titles/8368.html

Evidence of Minoan astronomy and calendrical practices

Authors: Marianna Ridderstad

(Submitted on 26 Oct 2009)

Abstract: In Minoan art, symbols for celestial objects were depicted frequently and often in a religious context. The most common were various solar and stellar symbols. The palace of Knossos was amply decorated with these symbols. The rituals performed in Knossos and other Minoan palaces included the alteration of light and darkness, as well as the use of reflection.

The Minoan primary goddess was a solar goddess, the ‘Minoan Demeter’. A Late Minoan clay disk has been identified as a ritual calendrical object showing the most important celestial cycles, especially the lunar octaeteris. The disk, as well as the Minoan stone kernoi, were probably used in relation to the Minoan festival calendar.

The orientations of the central courts of the palaces of Knossos, Phaistos, Mallia and Gournia were to the rising sun, whereas the Eastern palaces Zakros and Petras were oriented to the southernmost and the northernmost risings of the moon, respectively. The E-W axes of the courts of Knossos and Phaistos were oriented to the sunrise five days before the vernal equinox.

This orientation is related to the five epagomenal days in the end of a year, which was probably the time of a Minoan festival. One of the orientations of the Knossian Throne Room is towards the heliacal rising of Spica in 2000-1000 BCE. Spica rose heliacally at the time of vintage in Minoan times. The time near the date of the heliacal rising of Spica was the time of an important festival related to chthonic deities, the Minoan predecessor of the Eleusinian Mysteries.

The myths of Minos, Demeter and Persephone probably have an astronomical origin, related to Minoan observations of the periods of the moon, Venus and Spica. These celestial events were related to the idea of renewal, which was central in the Minoan religion.

Comments: 41 pages, 1 table, 14 figures

Subjects:

History of Physics (physics.hist-ph)

Cite as: arXiv:0910.4801v1 [physics.hist-ph]

Submission history

From: Marianna Ridderstad [view email]

[v1] Mon, 26 Oct 2009 12:31:24 GMT (1233kb)

http://arxiv.org/abs/0910.4801

Much as I would like these conclusions to be true, I’m afraid they are wishful over-interpretations by shoehorning of weak data. Little is known of Minoan symbols and nothing about Minoan rituals or what considerations went into the orientation of their palaces, except through the distorted mirror of myth or by heavy-duty archaeological inference.

“Five days before the equinox” is meaningless as coincidence and although Spica is a bright star, it’s not eye-catching compared with its neighbors. Also, its heliacal rising is too late in the year to signify the start of the wine harvest. As far as I know, the major Minoan goddess was not solar but either chthonic, broadly defined (Ariathne, Potnia Theron: All-Holy, The Mistress of Animals — similar to Ishtar or Cybele), or stellar/marine (Dhiktynna, The Starry Net, similar to Yemanja or Stella Maris).

I treat the Minoans as an Island civilization, disparate from all mainlands (Britannia is lucky it wasn’t walled in from the west).

Before reading your excellent essay, to which I shall now link, I put this on my Facebook page:

David Ruaune saw a programme last night about Thera, arguably the real Atlantis, and fell in love with their art, frescos and pottery, which seemed like the art of a free society – all flowing, sensual, women seeming strong and expressive, love of nature – I know I’m evading lots of theoretical issues, but that was the feel. I’m not much on visual art, but this stuff leaped out at me as beautiful.

Yes, hauntingly beautiful. And unique. A great pity the civilization didn’t get a chance to flower longer.

Monday, October 11, 2010

Harriet Boyd-Hawes…significant woman archaeologist

October 11th, 1871 to March 31st, 1945

Distinguished Women of Past and Present…

Harriet Boyd Hawes was the first archeologist to discover and excavate a Minoan settlement. She was born October 11, 1871 in Boston, Massachusetts, U.S.A. and graduated from Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts in 1882 (1892?).

After working as a teacher for four years, she started graduate work at the American School of Classical Studies in Athens, Greece. During her stay in Greece she also served as a volunteer nurse in Thessaly during the Greco-Turkish War.

She asked her professors to be allowed to participate in the school’s archeological fieldwork, but instead she was being encouraged to become an academic librarian. Frustrated by lack of support, she took the remainder of her fellowship and went on her own in search of archeological remains on the island of Crete. This was a very brave move, since Crete was just emerging from the war and was far from being safe.

Full article here:

http://philosophyofscienceportal.blogspot.com/2010/10/harriet-boyd-hawessignificant-woman.html

In addition to Harriet Hawes, another woman involved in Cretan archaeology was Alice Kober, whose hunches and deductions were critical in deciphering Linear B. Like Rosalyn Franklin in the DNA story, Kober died prematurely and with her crucial contributions unrecognized.

I enjoyed the essay particularly for the glimpse into Minoan civilization. That middle picture of the saffron gatherers is gorgeous.

That fresco is but one of many amazingly preserved ones from the Akrotiri excavations. All look truly ravishing and give tremendous insight into the culture. If you google the words Akrotiri frescoes, most of them will come up.