Steering the Craft – Reprise

Preamble: In October of 2010, I wrote an essay for the blog of Apex Magazine in response to a then-regular columnist’s whinings about “quality compromised by diversity and PC zombies” in life as well as speculative literature. Later on the Apex site was hacked, and its owner decided not to go through the laborious work of restoring its archive. In view of the recent discussions about women in SF (again… still…) and as a coda to The Other Half of the Sky, I’m reprinting the essay here, slightly modified.

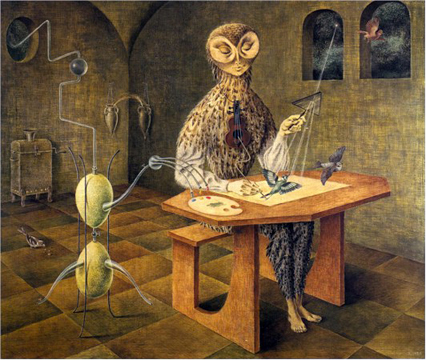

Remedios Varo, The Creation of the Birds (1957)

In honor of:

the Mercury 13 astronauts, who never got past the gravity well;

Rosalind Franklin, who never got her Nobel;

Shamsia and Atifa Husseini, who still go to school after the Taliban threw acid on their faces.

Cultural standards of politeness vary widely. In the societies I’m familiar with, it’s considered polite (indeed, humane) to avert one’s eyes from someone who has pissed himself in public, especially if he persists in collaring everyone within reach to point out the interesting shape of the stain on his trousers. At the same time, if he also splattered on my great-grandmother’s hand-embroidered jacket to demonstrate how he – alone among humans – can direct his stream, I’m likely to ensure that he never comes near me and mine again in any guise.

Yet I must still put time and effort into removing the stain from that jacket, which I spent long hours restoring and further embroidering myself. It’s not the only stain the garment carries. Nor are all of them effluents from those who used it and its wearers as vessels into which to pour their insecurity, their frantic need to show themselves echt members of the master caste du jour.

The jacket also carries blood and sweat from those who made it and wore it to feasts and battles long before I was born. Unless it’s charred to ashes in a time of savagery, probably with me in it, many will wear it after me or carry its pieces. Whenever they add their own embroidery to cover the stains, the gashes, the burns, they won’t remember the names of the despoilers. And when my great-grandniece takes that jacket with her on the starship heading to Gliese 581, her crewmates will admire the creativity and skill that went into its making.

So gather round, friends who can hoist a goblet of Romulan ale or Elvish mead without losing control of your sphincter muscles, and let’s talk a bit more about this jacket and its wearers.

If you insist that only sackcloth is proper attire or that embroidery should be reserved only for those with, say, large thumbs, we don’t have a common basis for a discussion. But I’ll let you in on a couple of secrets. I’ve glimpsed my nephews wearing that jacket, sometimes furtively, often openly. They even add embroidery patches themselves. And strangely enough, after a few cyclings I cannot guess the location of past embroiderers’ body bulges from the style of the patches or the quality of the stitches. I like some much more than others. Even so, I don’t mind the mixing and matching, as long as I can tell (and I can very easily tell) that they had passion and flair for the craft.

In one of the jacket’s deep pockets lies my great-grandmother’s equally carefully repaired handmade dagger, with its enamel-inlaid handle and its blade of much-folded steel. When I see someone practicing with it, on closer inspection it often turns out to be a girl or a woman whose hair is as grey as the dagger’s steel. They weave patterns with that dagger, on stone threshing floors or under skeins of faraway moons. Because daggers are used in dance – and in planting and harvesting as well, not just in slaughter. And they are beautiful no matter what color of light glints off them.

But before we dance under strange skies, we must first get there. Starships require a lot of work to build, launch and keep going. None of that is heroic, especially the journey. Almost all of it is the grinding toil of preservation: scrubbing fungus off surfaces; keeping engines and hydroponic tanks functional; plugging meteor holes; healing radiation sickness and ensuring the atmosphere stays breathable; raising the children who will make it to planetfall; preserving knowledge, experience, memory while the ship rides the wind between the stars; and making the starship lovely – because it’s our home and people may need bread, but they also need roses.

As astrogators scan starmaps and engineers unfurl light sails while rocking children on their knees, the stories that keep us going will start to blend and form new patterns, like the embroidery patches on my great-grandmother’s jacket. Was it Lilith, Lakshmi Bai or Anzha lyu Mitethe who defied the ruler of a powerful empire? Amaterasu, Raven or Barohna Khira who brought back sunlight to the people after the long winter sleep? Was it to Pireus or Pell that Signy Mallory brought her ship loaded with desperate refugees? Who crossed the great glacier harnessed to a sled, Sidney Poitier and Tony Curtis, or Genly Ai and Therem harth rem ir Estraven?

Our curiosity and inventiveness are endless and our enlarged frontal cortex allows dizzying permutations. We shape the dark by dreaming it, in science as much as in art; at the same time, we constantly peer outside our portholes to see how close the constructs in our heads come to reflecting the real world. Sometimes, our approximations are good enough to carry us along; sometimes, it becomes obvious we need to “dream other dreams, and better.” In storytelling we imagine, remember, invent and reinvent, and each story is an echo-filled song faceted by the kaleidoscope of our context. To confine ourselves to single notes is to condemn ourselves to prison, to sensory and mental deprivation. Endless looping of a single tune is not pleasure but a recognized method of torture. It’s certainly not a viable way to keep up the morale of people sharing a fragile starship.

In the long vigils between launch and planetfall, people have to spell each other, stand back to back in times of peril. They have to watch out for the dangerous fatigue, the apathy that signals the onset of despair, the unfocused anger that can result in the smashing of the delicate machinery that maintains the ship’s structure and ecosphere. People who piss wantonly inside that starship could short a fuel line or poison cultivars of essential plants. The worst damage they can inflict, however, is to stop people from telling stories. If that happens, the starship won’t make it far past the launchpad. And if by some miracle it does make planetfall, those who emerge from it will have lost the capacity that enabled them to embroider jackets – and build starships.

We cannot weave stories worth remembering if we willingly give ourselves tunnel vision, if we devalue awareness and empathy, if we’re content with what is. Without the desire to explore that enables us to put ourselves in other frames, other contexts, the urge to decipher the universe’s intricate patterns atrophies. Once that gets combined with the wish to stop others from dreaming, imagining, exploring, we become hobnail-booted destroyers that piss on everything, not just on my great-grandmother’s laboriously, lovingly embroidered jacket.

The mindset that sighs nostalgically for “simpler times” (when were those, incidentally, ever since we acquired a corpus collosum?), that glibly erases women who come up with radical scientific concepts or write rousing space operas is qualitatively the same mindset that goes along with stonings and burnings. And whereas it takes many people’s lifetimes to build a starship, it takes just one person with a match and a can of gasoline to destroy it.

It’s customary to wish feisty daughters on people who still believe that half of humanity is not fully human. I, however, wish upon them sons who will be so different from their sires that they’ll be eager to dream and shape the dark with me.

…like amnesiacs

in a ward on fire, we must

find words

or burn.

Olga Broumas, “Artemis” (from Beginning with O)

Susan Seddon Boulet, Shaman Spider Woman (1986)

Related blog posts:

Is It Something in the Water? Or: Me Tarzan, You Ape

SF Goes McDonald’s: Less Taste, More Gristle

The Andreadis Unibrow Theory of Art

Standing at Thermopylae

To the Hard Members of the Truthy SF Club

The Persistent Neoteny of Science Fiction

Beautifully written. And so true.

Thank you, dear friend!

Nicely done. 🙂

Thank you, Sabrina!

Eloquently written. If someone derides the capacity to empathize, to see the world from the differing contexts of people who are quite different from us, they seek to destroy what truly makes us human.

Exactly. Our imagination has kept us alive and made us who we are. The refusal to continue imagining may well destroy us, one way or another.

Thank you for this. I hadn’t read it before.

And thank you for the Olga Broumas poem, which I hadn’t read before either.

I’m happy you liked the essay, Genevieve! Olga Broumas is a force to be reckoned with.

Simply beautiful; no truer words.

Thank you, dear Heather!

Science fiction authors attack sexism amid row over SFWA magazine

SF writers’ association draws stinging criticism with chainmail bikini cover and articles praising Barbie and ‘lady editors’

guardian.co.uk, Wednesday 12 June 2013 09.24 EDT

http://www.guardian.co.uk/books/2013/jun/12/science-fiction-sexism-sfwa

It has made the internet rounds including an article with a stinging title at Adweek, but the responses on the Guardian and elsewhere show the depth and toxicity of the problem.

At least people are not remaining silent about the problem. That would be worse than just letting it slide.

It’s exhausting to see the problem pop up time after endless time.