Hidden Histories or: Yes, Virginia, Romioi Are Eastern European (and More Than That)

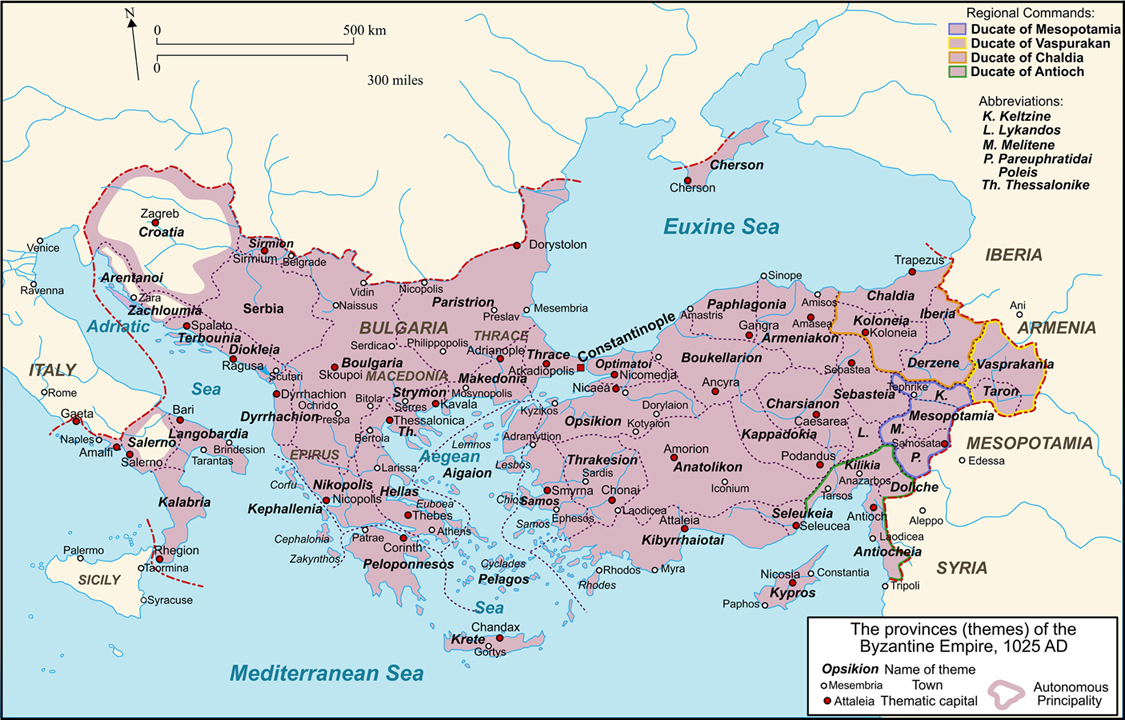

The Byzantine Empire, 1025 AD (medium extent)

[click on image for bigger version]

A slight variant of the article below first appeared in Stone Telling issue 1 (Sept. 2010) with the accompanying images in different internal locations. The reposting was triggered by two events but has been in my thoughts for a while, partly because of the recent fashionability of “hidden histories” in SFF. This directive considers “European-based” narratives undesirable as over-represented, shopworn, colonialist, etc. Like many western European history scholars, though for different reasons, the holders of this view (and, ironically, their ideological opponents) conflate “Europe” with its northwestern/central part and erase/ignore portions of European history that have always been unfashionable because they can’t be neatly slotted. Among those so erased are the Byzantines, who weren’t exactly a blink in history’s eye: they bridged east and west for a millennium. Yet on a rapid skim, I can count a single fantasy short story based on them, Christine Lucas’ “On Marble Threshing Floors” (Cabinet des Fées, Jan. 2011).

The shorter fuses that lit my decision to repost came from Twitter. One was an exchange with someone deemed a “scholar” in the SFF domain who informed me that “Greeks aren’t Eastern European, according to Wikipedia” (which makes me weep for the level of “scholarship” in SFF). The second was a link to someone’s article in which they called St. Basil of Caesarea “a Turkish bishop” again invoking Wikipedia as their authority – even though Logic 101, coupled with a modicum of historical knowledge, should have led them to wonder: a Turkish… bishop… in 330 AD?

So without further ado, here’s the article — a companion to Being Part of Everyone’s Furniture: Appropriate Away! and The Hyacinth among the Roses: The Minoan Civilization.

A (Mail)coat of Many Colors: The Songs of the Byzantine Border Guards

Today the sky is different, today the light has changed,

Today the youths are riding out to join in the battle.

— Start of The Song of Armouris, the oldest Akritikón

In the first chapter of Mary Renault’s The Persian Boy, enemies overrun the protagonist’s mountain fortress home. Rather than suffer the usual fate of captive women, his mother leaps to her death from the parapet. Western readers considered this a dramatic gambit, but to me it was routine fare: I had already encountered it in the history and folksongs of my people; prominently so in the Akritiká, the songs of the Byzantine border guards.

The common view in the West is that the Roman Empire fell in the fourth century, when it was overrun by the Goths, Vandals and Alans. In reality, only the western half disappeared under the waves of invaders. The eastern portion became a great multicultural empire that lasted a thousand years, acted as both a buffer and a bridge between Asia and Europe, and gave the Rus Vikings of Kiev the Cyrillic alphabet. Instead of Latin its lingua franca was a Greek evolved from the Alexandrian koiné, and its dominant religion was Orthodox Christianity. Renaissance scholars called it the Byzantine empire, but its citizens called themselves Romioí, Romaíoi – Romans – and they retained much from the older empire.

One of the Roman customs that the Byzantines kept was the entrusting of their eastern border defense to local militias in addition to the professional army. Ákron is the Greek word for “edge” – so these guards became known as Akrítai. In exchange for their service, they received small land holdings and tax exemptions. Not surprisingly, they were an ethnic and religious kaleidoscope. They were Greek, Armenian, Syrian, Bulgar, Thracian; they intermarried, changing religions as they did so. Usually they acted as guards and scouts, sometimes becoming the brigands they guarded against. They reverted to farming whenever the din of war subsided, though that never lasted long for them to put away their weapons.

From the 8th to the 10th century, the Akrítai were instrumental in checking Arab incursions into Asia Minor, from Syria to Persia to Armenia. They helped the Byzantine army push back the formidable armies of the Damascus Caliphate. They became crucial again in the Black Sea Byzantine empire of Trapezous (Trebizond), founded after the Crusaders sacked Constantinople in 1204 in their zeal to punish those the Pope declared schismatics (the Byzantines compounded their unnaturalness by giving some power to women and “effeminate” men and they also happened to possess astonishing riches as well as decadent habits, such as using forks).

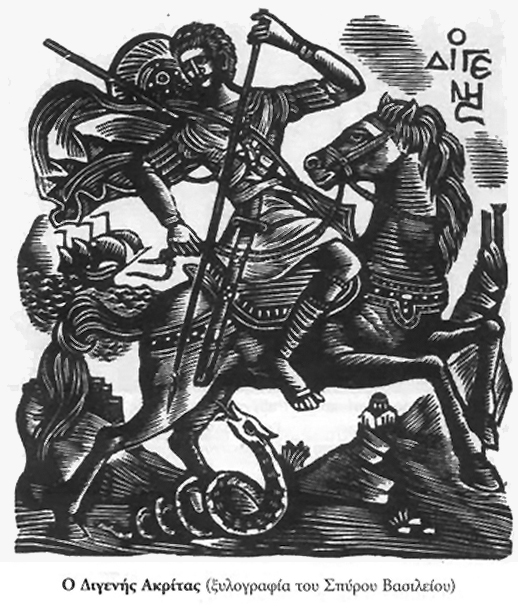

From this liminal zone at the edge of the empire arose the earliest Greek folksongs to survive till our days: the Akritiká. The earliest versions hail from the 9th century. Some scholars consider them the beginning of modern Greek literature. The main figure in them is Diyenís (Two-Blood) Akrítas, a cultural hybrid representative of his entire group.

The songs tell that a Saracen emir kidnapped the daughter of a Byzantine general. Her five brothers hunted him down and the youngest challenged him to a duel, the prize being his sister’s freedom. The emir was defeated, but he had fallen in love with her. To keep her, he decided to convert to Christianity and live among her people. Diyenís was the child of this marriage. The lays of the exploits of Diyenís and the other Akrítai are equal parts Homeric saga and chanson de geste – and like them, they were sung by wandering singers (ayírtai) kin to troubadours.

The songs thrum with thirst for honor and glory, attainments that obsess men in such settings: the heroes swear unbreakable oaths, avenge murders and kidnappings of kin, duel and become blood brothers with worthy enemies, receive counsel from faithful horses and prophetic birds, fight entire armies single-handed, slay preternatural beasts. In deeds and attributes they are close to Herakles, Achilles and Cuchulainn, even to the extent of the berserker fury that can possess them in the heat of battle. These echoes have deep and tangled roots. The Akrítai not only lived and died on the plains of Hector’s Troy and the hills of Medea’s Colchis, but long ago the locals had also absorbed the Celts that once comprised the Anatolian nation-state of Galatia.

The songs also echo with laments about courtship and star-crossed love, loveless marriage and abusive in-laws, devotion or hatred between children and (step)parents, enslavement, exile. Through these preoccupations, the other half of humanity appears in the Akritiká. Byzantium was a stiffly patriarchal society that deemed women inferior, temptresses if not controlled. Nevertheless, its women were better off than their Roman, Frankish or Slav counterparts. They did not suffer the inequities of Salic law: they owned their dowries and were equals in inheriting and bequeathing property and status to their children; they could own businesses, be heads of households, even Emperors; and they were at least basically literate, while the upper class produced several female scholars and historians whose works are still studied today.

Young women in the Akritiká are invariably single daughters, prized and cosseted. The apple of their parents’ eye, they are surrounded by an army of devoted brothers. Perhaps the most famous Greek ballad, The Dead Brother’s Song, begins: “Mother with your nine sons and with your only daughter/ Twelve years she had reached and the sun had not touched her/In the dark her mother bathed her, in the dark she combed her/By moonlight and starlight she braided her hair.” A woman’s brothers drop everything to defend, rescue or avenge her.

Although Byzantine marriages were usually arranged, the Akritiká sing the praises of romantic love, just like the courtly love lays they resemble. Their heroines are often kidnapped (sometimes in raids, sometimes by a smitten spurned suitor) but equally frequently they elope with men whose singing or looks they like – as Yseult did with Tristan. The Akritiká also reflect the fact that women wielded real authority in the household. They marked their children’s lives by blessing or cursing them and, as with the Iroquois or contemporary jihadis, only mothers could give their sons permission to go to war.

Women’s power partly arose from the constant war footing of the society portrayed in the Akritiká. It is a sad fact that women’s status is often higher in warlike societies, from the Spartans to the Mongols: they have to keep everything going when the men are absent or dead. In the case of the Akrítai, there was an additional wrinkle. The Byzantine border populations came in touch with the more matriarchal (or at least less patriarchal) Scythians, Sarmatians, Phrygians and Lydians. Around the Black Sea, archaeologists have been excavating kurgans that contained skeletons adorned with jewelry and mirrors – but also with daggers, javelins, quiverfuls of arrows and weapon-inflicted notches on their bones. These tomb occupants merited human sacrifices and their pelvic angle leaves no doubt that they were female, once again vindicating Herodotus whose descriptions tally with the findings.

Women’s power partly arose from the constant war footing of the society portrayed in the Akritiká. It is a sad fact that women’s status is often higher in warlike societies, from the Spartans to the Mongols: they have to keep everything going when the men are absent or dead. In the case of the Akrítai, there was an additional wrinkle. The Byzantine border populations came in touch with the more matriarchal (or at least less patriarchal) Scythians, Sarmatians, Phrygians and Lydians. Around the Black Sea, archaeologists have been excavating kurgans that contained skeletons adorned with jewelry and mirrors – but also with daggers, javelins, quiverfuls of arrows and weapon-inflicted notches on their bones. These tomb occupants merited human sacrifices and their pelvic angle leaves no doubt that they were female, once again vindicating Herodotus whose descriptions tally with the findings.

So women in the Akritiká are not just the “Angels (or Demons) in the House” but appear in yet another guise: as warrior maidens who hold besieged castles and best all men but the hero in single combat. Taking his cue from his Bronze Age confrères (Theseus and Hippolyta or Antiope, Achilles and Penthesilea) Diyenís almost finds his match and soulmate in the Amazon Maximó, a renowned fighter and the leader of her own band. But the more common tropes and mindsets prevail: the encounter ends with her rape and/or murder – and the warrior maidens in the Akritiká either fall to their death (just like Bagoas’ mother in The Persian Boy) or become diminished consorts to their conquerors. Just like the real-life sworn virgins of the Balkans, the women, unlike the men, can only have half a life.

Death, often chosen, awaits the women who cross boundaries. Death is also where the pagan bedrock surfaces in the Akritiká. If illicit lovers cannot reconcile their kin to their decision, they invariably die by suicide, the church teachings ignored. And the afterlife in these songs is not the Christian or Moslem garden of delights, but the dank, dark underworld of The Odyssey and of Ursula Le Guin’s Earthsea. When Charon (Death) comes for Diyenís, he comes as the warrior whom none can withstand. For three days and three nights the two clash on a stone threshing floor. But Charon always wins, and the hero knows this when he agrees to the duel. The goal is to maintain honor by giving him a good fight. As a final shamanistic turn, the hero’s blood brothers dance and sing around him fully armed while he dies, defiant to the end.

Inaugurating the major shift from the older dactylic hexameter, the Akritiká are in blank verse iambic heptameter: fifteen syllables with a caesura after the eighth one. The style is known as “politikón” (civilian – that is, secular) or “galloping chariot” because of its rhythm. Like the British Border ballads, the songs are unadorned and straightforward, with barely any adjectives or adverbs. They also have a strobe-light effect, highlighting some telling minute action but compressing large swaths of events into a few words. The songs are sung either a capella or with a flourish-free instrumental background – usually the three-string Cretan or Pontian lyre (known as the kemenché to those familiar with World Music albums by Peter Gabriel or Yo-Yo Ma).

Just as the Akritiká were birthed at the borders of Byzantium, so did they persist there. While the rest of the Byzantine territory evolved different songs under Ottoman rule, the Cretans, the Cypriots and the Pontians of the Black Sea continued to sing them. From those peripheries, always more culturally conservative than the center, the lays survived to our days, shards of once great diadems. My people used the Akritiká as rallying cries during times of oppression – the Ottoman era; the German occupation and the resistance to it during WWII; the military junta of the sixties. I was raised and nourished on them. They run and murmur in my veins with all their glories, blind spots and contradictions.

The time has come to let the songs themselves take center stage. Included is a Cretan rendition of the Death of Diyenís by the famous singer and lyre player Níkos Ksiloúris (who, like Diyenís, fought Charon at the flower of his maturity). Here is a bare-bones translation of the text:

Diyenís struggles for his soul and the earth is frightened.

And the gravestone shudders — how shall it cover him?

As he lays there, he speaks a brave man’s words:

“If only the earth had stairs and the sky chain links,

I would step on the stairs, seize hold of the links,

Climb up to the sky and make the heavens quake.”

Sources and further reading/listening (partial list):

John Julius Norwich, Byzantium – The Early Centuries, The Apogee, The Decline and Fall

John Julius Norwich, Byzantium – The Early Centuries, The Apogee, The Decline and Fall

Neal Ascherson, The Black Sea

Christódoulos Hálaris, Akritiká – Odes of the Byzantine Empire Border Guards vol. 1 and 2

Images within the article:

Diyenís Akrítas, woodcut by Spiros Vassiliou

Amazon, Attic white-figure vase, 470 BC, British Museum

Armed Pontian Greeks dancing to the lyre, Trabzon, 1910

Fascinating post, Athena! I’ve been interested in the Byzantines for a long time. When I first read about the decline and fall of Rome, it became clear to me that Rome didn’t “fall” flat so much as it split in two and then fell in the western half, leaving the Eastern half to carry on as the Byzantine Empire.

I had not heard of the Akritiká before- I must find out more about it. Thanks for the source list!

Thanks for taking the time to write this out.

Judith Tarr’s ‘Hound and Falcon’ trilogy starts in Britain but Byzantium plays a major role in it. I seem to recall that she wrote at least one other book with that setting, and she’s definitely borrowed from it.

Since the Hound and Falcon was one of the first fantasy series I read, and one of the things that deepened my interest in history, I’ve always regarded Byzantium as equal successor to Rome.

I’m fairly sure Guy Gavriel Kay based one of his books on Byzantium, but he’s borrowing from everywhere, so that doesn’t mean anything.

Glad you enjoyed it, Christopher! Yes, it’s befuddling to run headlong into total ignorance about the Byzantine Empire, given how important it was.

A very good historical fiction source for this era is Ismíni Kapádai. Unfortunately, I think most of her works have not been translated into English.

You’re right, my long-term memory had chosen to forget Kay’s Sarantine Mosaic diptych, which I found a mediocre, annoying mess. It takes place in an equivalent of Justinian and Theodora’s time, with the iconoclast era telescoped in. The only thing I recall clearly was that all the women in the story were desperate to have the Gary Stu mosaicist’s babies, including the Empress (!).

I haven’t read Tarr, I should look into that trilogy. I was focusing on short stories when I did my quick mental survey. In the larger picture, Byzantium is essentially absent in “European-based” fantasies, whether “progressive” or “regressive”.

Illuminating post; it’s all the more interesting to learn about the lesser known aspects of Byzantium – namely the Akritiká – when they’re given little or no mention in a fair amount of material.

Thanks for the sources!

It’s those tiny corners that make cultures (past or present, real or invented) come to life — and become interesting!

Very interesting.

I can’t remember if Jacqueline Carey’s heroine Phedre visits an alternate Byzantium / Constantinople. She travels all over Europe and beyond, but I don’t recall a stop there. Do you?

Phèdre, as peripatetic as Dunnett’s Lymond, does visit that part of the world, but Carey posits a longer-lived Minoan polity that, incongruously, practices “Greek love” as defined by Westerners (recall that her entire universe is pagan, even the Hebrew variants, so Byzantium would not fit the narrative framework).

Yes, I figured “Constantinople” was a contradiction in her world, but I couldn’t remember if she visited the city on that site. Anyway, thanks for reminding me how she handled it.

Byzantines are the villains in Sprague deCamp’s Lest Darkness Fall.

Harry Turtledove’s short story collection Agent of Byzantium.

Cecelia Holland set one of her dreary Corban Loosestrife fantasies in Constantinople, according to Wikipedia. But her historical Belt of Gold in my opinion is actually good.

I liked Holland’s Jerusalem (less so her Great Maria — she fumbles with women characters and I suspect the same will be the case with Belt of Gold).

All the works you list are twenty or more years old. It’s interesting that Byzantium vanished completely in the era of “grittygrotty” and “social justice” fantasy, both purporting to deal with realism and/or complexity.

If the Roman Empire had survived, do you think we would now have cars like the Jupiter 8 and television programs called Name the Winner? :^)

They had their own vulgar streaks, like all cultures — so variants like what you suggest are quite possible!

John M. Ford’s _The Dragon Waiting_ has a non-Christian Byzantium ruled by the vampires Justinian and Theodora – but it is mainly off-stage IIRC. The non-SF biggie for me as a young reader was Graves’s _Count Belisarius_.